GEOGRAPHIC EXTREMES SOCIETY

AUSTRALIAN RECORDS

Australia’s worst pollution

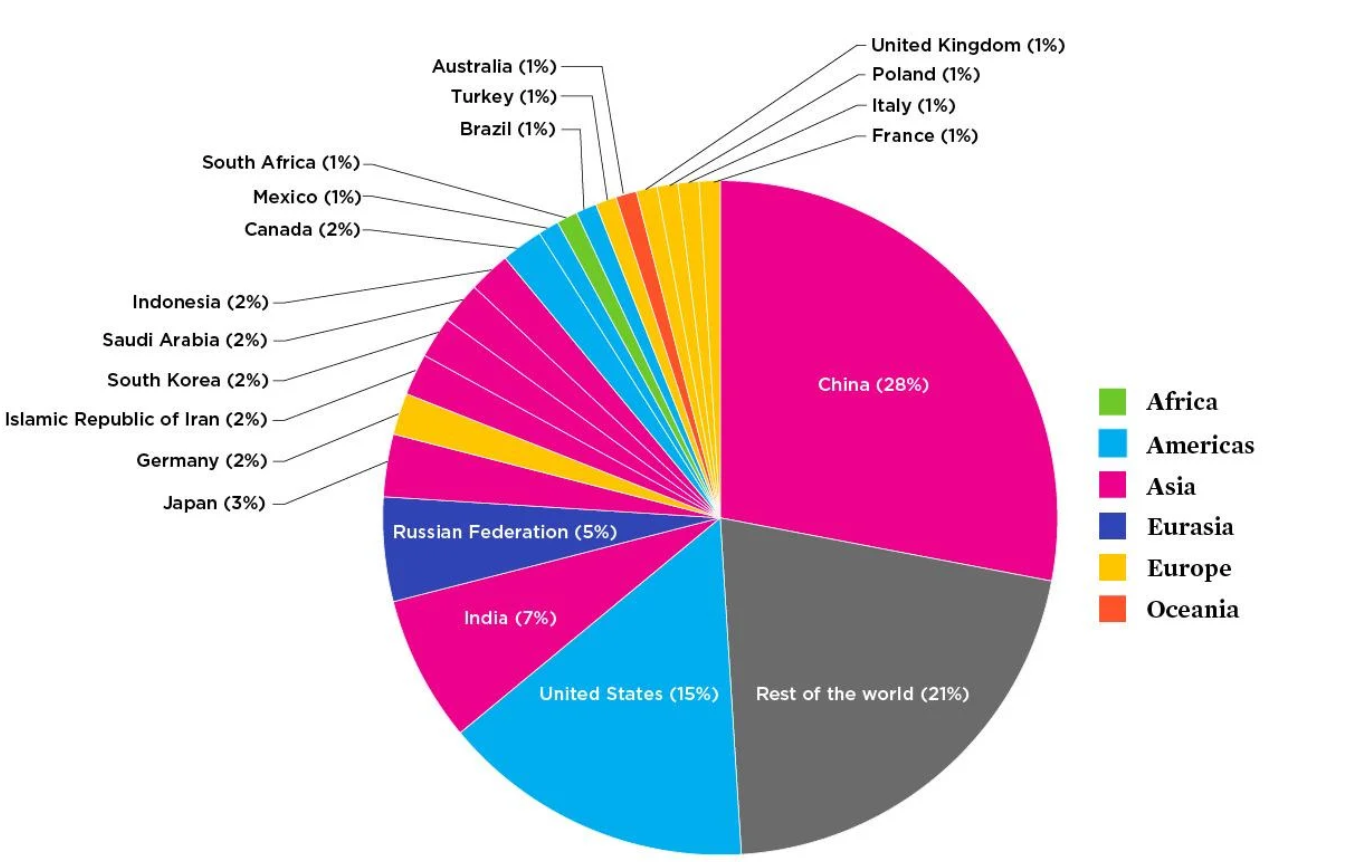

Compared to many countries around the world, I’m pleased to say that Australia is a country where there are strict controls on man-made pollution, and, overall, the environment remains relatively clean. Pollution rarely affects Australians in their backyards, due mainly to the large size of the country compared to the relatively small population. In 2018, Australia ranked 16th in the world for CO2 emissions, above countries in Europe like UK, France and Italy.

Australia’s Share of Pollution. Image: Union of Concerned Scientists

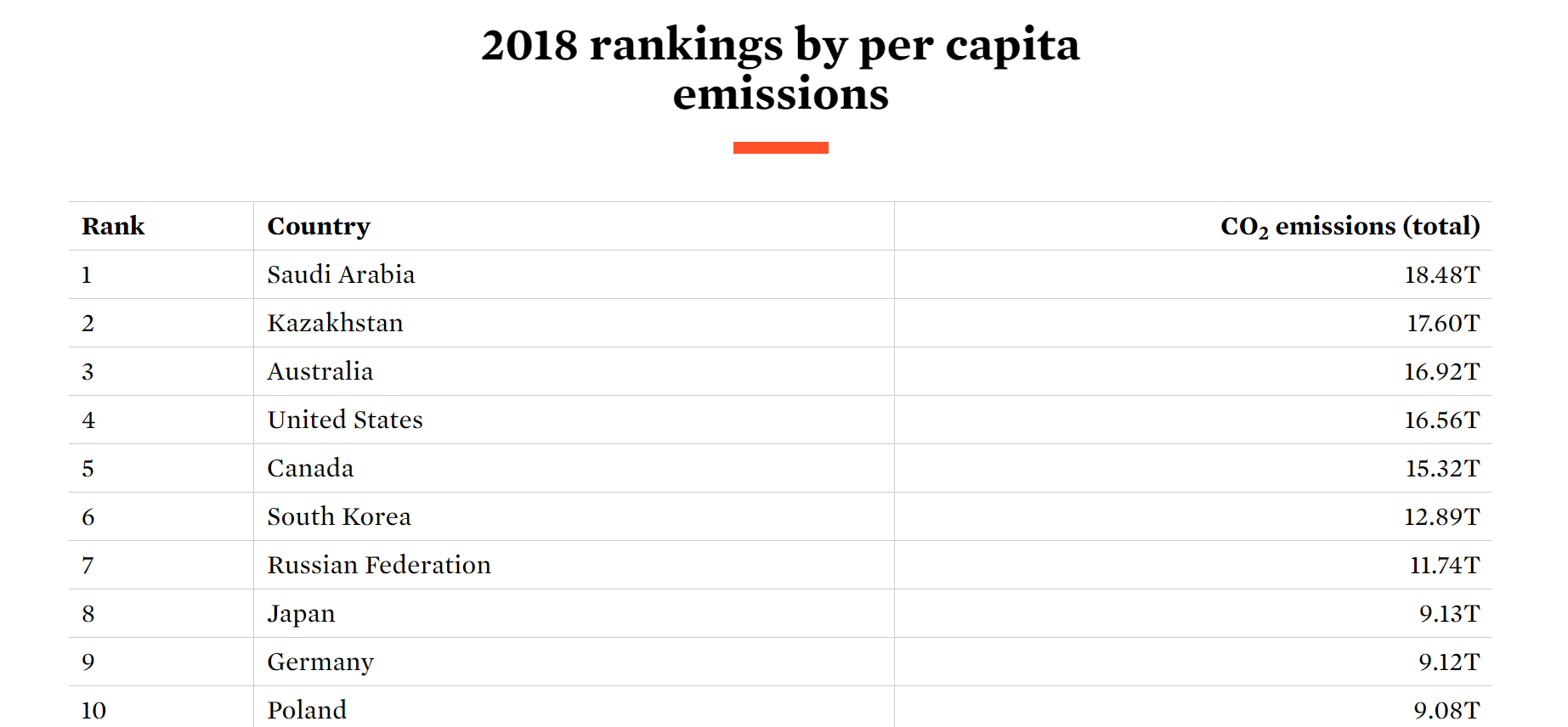

However, this contrasts sharply with Australians on a per capita basis, have one of the highest pollution footprints in the world. There are many cars, large houses complete with an abundance of appliances and useless gadgets, and most of us rely on coal-fired power stations for our electricity supply. Thankfully, in this regard at least, most Australian coal that we export and use domestically, are low in sulphides and only account for 1% of worldwide sulphur dioxide emissions.

Emissions Per Capita CO2. Image: Union of Concerned Scientists

Sulphides Pollution

Australia’s pollution report card isn’t perfect and there have been a couple of heinous examples of sulphide pollution in Australia.

Sulphide emissions per capita. Image: Our World in Data

In Queenstown, and to a lesser extent in nearby Zeehan, a century of copper mining and smelting inflicted significant damage and visible scars which still remains upon the landscape.

Queenstown and Mount Lyell Mine pollution. Image: Driussi. 2006

Starting in 1893, the copper smelting in this region released thick, toxic plumes of sulphur dioxide gas into the atmosphere, which quickly killed all the temperate rainforest, native animals, fungi, and pretty much every other organism, downwind of the smelter plumes. The sulphur dioxide quickly metabolised to form a sulphuric acid mist, which drowned everything to leeward in a toxic haze. As the plants died from the sulphuric acid laden rain, the massive rainfalls and runoff, washed away the topsoil, leaving only bedrock.

Queenstown’s barren hillsides have been extensively chronicled by photographers for over a century and held up as an example of what not to do when smelting copper. Pristine temperate rainforest once cloaked the hillsides around the township, which lies on the doorstep of the famous Southwest Tasmanian Wilderness Area. Today, the smelters and most of the copper have gone. Unfortunately, as a result of the mining, so has the native vegetation.

Today, very few pioneer plants can regenerate in the area – a few acacias and one or two fern species struggle to gain a foothold. Centuries will need to pass before soils once again establish with the assistance of our bacterial friends.

Most Polluted River in Australia

Queenstown’s, Queen River, is also known to locals as the Red River or Pumpkin Soup Creek depending on the concentration of tailings minerals washing through the system. The Queen River meets up with the once-pristine King River to form what is arguably still the most polluted river in Australia.

Queen River running through Tasmania’s South West wilderness. Most polluted river in Australia. Image: KK Gypsies

Over the century of mining operations, an estimated one hundred million tonnes of tailings were released into the Queen and King rivers. The King River eventually makes its way into beautiful Macquarie Harbour close to Strahan, which ranks as one of the most picturesque towns in Australia. Those aboard Macquarie Harbour tour boats can view the estuary of the King River and the associated sediments built up at its entrance. The inlet seems to have weathered the impacts of the pollution quite well, but when our boat cruised past the salmon farms, I wondered what effects linger here. I’m sure the salmon farms test for contamination, but the century-long flow of mine tailings would undoubtedly enter the Macquarie Harbour ecosystem.

Most polluted locality in Australia.

Yet, it’s Mount Isa, in north-west Queensland, which tops the list as the most polluted postcode in Australia. Tailings dams, slurry pits and sulphuric acid fallout from the smelting chimneys of Mount Isa all combine to destroy most lifeforms downwind of the copper, zinc and silver smelters. The country surrounding Mount Isa is a rough and rugged landscape. It’s arid, rocky, hilly, parched and for most of the year, very, very hot. To their credit, the locals of Mount Isa have created an oasis in this harsh terrain. The town lies to the east of the mine, and no one lives to the west due to prevailing winds. The Mount Isa Mines operates a sophisticated, world-class warning system to warn residents of an impending wind change that may have caught the smelter operators off guard.

As part of their environmental policy, Mount Isa Mines monitor the toxic plume from the smelters for 236 kilometres before determining that the sulphur dioxide is diluted enough not to pose a threat to any species living downwind.

Most of Australia’s sulphide pollution comes from human-made processes, but there are some formidable examples of nature unleashing its own toxic compounds. For example, acid sulphate soils can trigger massive vegetation dieback once unearthed and exposing them to oxidation. The exposure of these soils can occur with cyclones, erosion from rivers, waves and currents, but still, it remains that humans are predominately responsible for the unearthing of acid sulphate soils. Humans can also be responsible for exposing other damaging materials like the mining of asbestos ore, drilling for petroleum products, and pumping of mineral-laden groundwaters to the surface. Nationally, an estimated 40,000 km2 of Acid Sulfate Soils are found in coastal environments and Queensland has the greatest concentrations of over 23,000 km2

Radioactive pollution

Radiation may cause some of the most ghastly injuries, but the truth is, radiation is all around us. It’s in the food we eat, the earth we stand on, and in background radiation emanating throughout the universe. Our planet would be as barren as Mars if it weren’t for Earth’s electromagnetic field, which continually repels solar winds from our Sun. Without this defence system, these solar winds would have the ability to strip the atmosphere and protective ozone layer and expose the surface to intense ultraviolet radiation.

The type of radiation that worries most of us, and that which can cause strange mutations and death, is ionizing radiation. This is measured in a few ways, but most commonly millisieverts, abbreviated to mSv. In Australia, the average person’s yearly dosage from this background radiation is 1.5mSv. Physicians tell us that you need a dose of about 1,000 millisieverts to increase your risk of cancer by about 5%. The average CT scan delivers about 10millisieverts, whereas treatment for leukemia would come in around the 250 mSv. Looking at the top end of the scale, a dose of 5,000millisieverts would kill half of those exposed to it within a month.

Uranium mining started in Australia with mines at Radium Hill in 1906 and a few years later at Mount Painter, both in South Australia’s Flinders Ranges. The Radium Hill Mining Company extracted the ore, sending it to a processing plant on the foreshores of what is now the affluent suburb of Hunters Hill in Sydney. A recent New South Wales Government report documents the disposal of wastes from the uranium refinery at Hunters Hill, and it makes for a very sobering read. It lists examples of forty-four-gallon drums full of radioactive waste spilling, and sometimes just dumped into Sydney Harbour. Initially, radioactive waste was kept on-site before transported to controlled dumping sites. More worrying still, a significant amount of unaccounted-for tailings were removed off the site and dumped in unknown areas around Sydney. The Radium Hill Mine closed in 1914, followed closely by the Hunters Hill refinery.

After WWII, the British Government decided it would be a good idea to buy freshly-mined Australian uranium, turn it into nuclear weapons, and then test it in a convenient, friendly Commonwealth country with lots of open spaces. Menzies gave the go-ahead for the British to detonate as many nuclear devices as were necessary, but with a restriction of fifty kilotonnes for a single explosion. This restriction excluded the use of the hydrogen bomb/thermo-nuclear weapon testing.

On October 3, 1952, Britain joined the atomic bomb club when a nuclear explosion was detonated in the Montebello Islands off Western Australia’s Pilbara coast.

The British returned to the Monte Bello Islands and secretly detonated a 60 Kiloton weapon on June 19, 1956. On June 21 atomic fallout fell throughout Queensland. A prospector looking for radioactive ores near Cloncurry was boiling his billy to make a cup of tea when all of a sudden, his Geiger counter started going berserk. In Brisbane, a company developing Geiger counters for the mining trade, suddenly saw their devices go haywire. As the thyroids of animals came in for testing over the next few weeks, results showed that the iodine 131 levels were up to 4,000 times greater than should be expected. Radioactive Iodine gets concentrated in the thyroids of humans and other animals, with its destructive effects usually felt later in life.

The British once again began testing in the latter half of 1956 in South Australia. The third Maralinga explosion on October 11, 1956, was one of the smallest, but the one that had the most significant impact on Australia’s population. The meteorological forecasts were good at first, but a few minutes after the explosion the anticipated wind direction changed earlier than had been expected, and the radioactive plume drifted over Adelaide and headed towards Melbourne. Air sampling found that radioactive material fell over Adelaide and throughout that state’s south-eastern region. The fallout continued over to Melbourne, where the entire state of Victoria was drenched in radioactive material. New South Wales, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory were also completely covered in fallout. Neither the people of Adelaide, nor the rest of Australia, were told of the situation, and the truth would only emerge decades later.

Radioactive fallout from Buffalo 3 test. Image: Butement 1958

With the radioactive fallout precipitating across vast areas of south-eastern Australia, the Strontium-90 settled onto the ground and coated plants and animals a fine layer of radioactive film. Strontium-90 is further concentrated when herbivores consume those plants. Of particular concern is when dairy cattle ingest the Strontium-90-covered grasses, as this results in the radioactive chemical attaching to calcium molecules in milk,

Here the story takes a dark twist. At that time, the Australian government’s health policy included providing 300ml milk bottles to all children in Australian schools. From 1957-58, the bone samples of four hundred Adelaide-based children who had died were analysed for Strontium-90. Every single sample came back positive.

In 1963 when the world’s nuclear powers became aware of the dangers posed by releasing Strontium-90 in above-ground atomic tests. It was all too late for Australia, but nuclear nations agreed to stop atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons and went underground.

The most lingering problem, however, wasn’t the twelve atomic blasts inflicted on Australia. In smaller associated trials, codenamed Vixen A and Vixen B, held at Maralinga’s, Taranaki testing site, the British unleashed the worst of Australia’s radioactive incidents. The most significant nuclear contamination issues occurred when testing how stored nuclear weapons reacted to fires and explosion.

In the Vixen trials, considered minor at the time, the British unleashed what we today would call a ‘dirty bomb’. Dirty bombs infected the surrounding area with an intense dose of radiation. Although this wasn’t the British nuclear agency’s intentions at Maralinga, it nonetheless had the same effect. Around 23kg of Plutonium-239 was set on fire and a radioactive fire plume hundreds of metres high released Plutonium into the surrounding Taranaki testing range.

Plutonium, if left alone, can be relatively harmless and your skin will repel most of the alpha radiation released. It’s when Plutonium enters the body, through eating or when breathed in, that plutonium radiation becomes lethal.

How does Plutonium become airborne for people to breathe in? In dust storms, of course. Radioactive-laden soils from old British nuclear test sites at Maralinga have been lifted into the atmosphere and swept eastwards within the plumes of dust. South Australia’s deserts have contributed much in the way of clouds of dust which have passed over the eastern seaboard since the 1950s, and there’s little doubt that these would have contained radioactive materials within the dust storms.

2009 Sydney Dust Storm. Plutonium 220 was raised in storms similar to this. Image: ABC

Anyone like myself, who has lived through the spring dust storm which turned Sydney a foggy-red colour in 2009, will know that it’s easy to breathe in this dust. The 2009 dust storm was the largest Australia has recorded. The Millennium Drought, one of Australia’s worst-ever, had ravaged the country from 2001 to 2009, and that spring of 2009, an intense cold front swept across southern Australia sending the dust and soil airborne. The dust storm swept over the eastern states and out into the Tasman Sea.

Eleven years after testing began, the British nuclear agencies realised the impacts and in 1967 attempted to clean the site. Codenamed ‘Operation Brumby’, they removed topsoil at the test sites and remixed it with other soils, and buried the most contaminated soils in trenches. The British deemed the site safe, with the Australian government dutifully signing off on the clean-up and, remarkably, releasing the British government from any further future liability.

A tour through the cemetery at nearby Woomera is a startling reminder of the death toll on young children born at this time. Of the babies born in the Woomera hospital between December 1953 and September 1968, twenty-three were stillborn, and the cemetery contains a further forty-six graves of other children who died within this period.

In 1995, the McClelland Royal Commission declared its findings into the 42 British Nuclear tests performed in Australia. At Maralinga, 30% of the British and Commonwealth nuclear weapons test veterans died from cancer-related illness, the majority only living into their 50s [7]. The British Government compensated its servicemen, and the Australian government made compensation to a select group of cancer patients. A thorough clean-up at Maralinga cleared the dirty plutonium explosion from the Taranaki testing site at Maralinga. This included treating the majority of the topsoil before burying it into concrete-topped slit trenches, to be sealed for many thousands of years. In 2000 the Maralinga testing sites were eventually deemed safe, and in 2009 it was handed back to its traditional owners.

In Australia, Paralana Hot Springs in the northern Flinders Ranges has the highest natural radiation risk. The South Australian Heritage Register lists Paralana Hot Springs as a designated place of geological significance. I’ve seen publications rating the hot springs as the 13th most naturally radioactive place on Earth [6]. The Radon Gas which bubbles to the surface disperses quickly into the atmosphere with little or no effect to the surrounding environment. The only possible contaminating effect comes during still days when there is no wind. Radon gases can settle into the lowest depressions and any sustained breathing of Radon rich-air can cause serious health issues in later life.

Gas bubbles containing Radon. Paralana Hot Springs. Image: Mapio

Pollen Pollution

It may surprise many Australians to learn that the continent’s most fatal pollution event wasn’t from radioactivity, nor mercury-laden plumes from refineries, nor clouds of sulphur dioxide residue falling on towns. On Monday, November 21, 2016, the worst single pollutant event happened in Australia, with the Emergency Services hotline receiving the highest number of phone calls in a 12-hour period, on record.

On that day, Melbourne was lashed by a large thunderstorm bringing winds of over 100km/h, which were then followed by a dramatic cool change that saw temperatures drop by fifteen degrees in fifteen minutes. Ten Australians died during this event, and over 3,000 people presented to Melbourne hospitals with acute symptoms. The culprit? Allergic reactions to grass pollen. The world’s most catastrophic Thunderstorm Asthma Epidemic paralysed Melbourne’s emergency services during the two hours it took for the thunderstorm to pass,

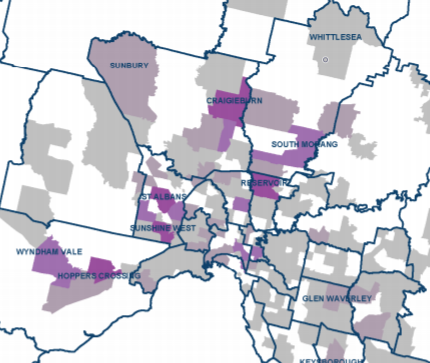

Thunderstorm Asthma Epidemic hotspots. November 21-22, 2016

It wasn’t long after the storm passed that the perpetrator of the asthma-inducing pollen was identified: the widely used, imported grass known as perennial ryegrass. Native to Europe, the Middle East and the Mediterranean region, this grass has been introduced into Australia for many decades and used in a wide range of applications. Today, it has established itself as a major weed on roadsides, footpaths, sand dunes, riverbanks, sports fields and extensive agricultural areas. The grass has countless admirers and not only in the farming sector. It is the ‘hallowed turf’ used at the All England Tennis Club for Wimbledon, and also used for wickets and the outfields at the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

Perennial ryegrass has long been recognised for its prolific pollen count and associated with hay fever-like symptoms. However, no one saw the pollen storm of November 2016 coming. Emergency phone lines were jammed. Emergency Services estimated that the 000 number would usually get twenty-nine calls per hour at that time of the year, yet on that evening in Melbourne, from 6 pm until 6 am, over 1,200 emergency calls were received. Ambulance systems could not cope, and the hospital system went into meltdown with 3,365 cases associated with the Thunderstorm Asthma Epidemic presenting to Emergency Departments. Medications ran out at 24-hour pharmacies, and Ventolin was sourced from further afield.

So, what environmental factors contributed to such an enormous outbreak? Southern Victoria had just experienced its tenth wettest spring on record and grasses everywhere were seeding and proliferating. There was little warning of what was to come, as pollen counts had been normal in the week leading up to the epidemic, but an extremely high pollen count had been recorded in the first week of November.

Pollution Records

GES Record: Most polluted river in Australia – King River. Tasmania (Source: Cool Australia.org)

GES Record: Most polluted area in Australia – west of Mount Isa City (Source: ACF National pollution inventory Report 2018)

GES Record: Largest Atomic test. Montebello Islands. Operation Mosaic 2. June 19, 1956. The equivalent of 60 Kilotonnes of TNT. (Source: Aust Dept of Veterans Affairs)

GES Record: Most naturally radioactive locality – Paralana Hot Springs. The highest concentration of 226 Ra was 29,000 Bq/L. (Source: Antitori 2002)

GES Record: Largest single pollutant event in Australia. November 21, 2016 Melbourne thunderstorm asthma epidemic. (Source: RJ Andrews)

The Geographic Extremes Society welcomes any input as to the veracity of these records and we encourage everyone to contribute to these extreme records by contacting us to initiate the discussion