GEOGRAPHIC EXTREMES SOCIETY

AUSTRALIAN RECORDS

Waves

Some of the world’s greatest waves crash into the southern Australian coastline. This is where the currents of the Southern Ocean oscillate around the globe, relatively unhindered by land and where waves are pushed along by the winds of the roaring forties, furious fifties and screaming sixties.

the world’s biggest waves converge on those select reefs, To understand these waves, a knowledge of how the shape of the seabed forces waves to rear up to incredible heights. When you hear them discuss their art, you quickly understand that they are conversant with complex interactions of wave amplitude, wave speed, tidal influences and wind effects.

In Australia, there are a few renowned surf breaks that resonate with this ever-growing band of adventure seekers. Names like The Right, Ships Stern, Pedra Branca, Ours and Cow Bommie, among others are altogether unfamiliar to the vast majority of us, sounding like code for a military operation.

Australians love their beaches, especially when adorned with crashing surf. Surfable waves, capable of being surfed, stretch from the Town of 1770 in Queensland, along the continent’s southern coast to North-West Cape in Western Australia. Large waves are only generated on Australia’s protected northern coastline when cyclones pass through, or when surfers venture far offshore to Queensland’s Great Barrier Reef.

Most Australians have an affinity for surf and waves because we are coastal people. In 2001, the Australian Bureau of Statistics produced figures which revealed that 84.7% of Australians live within 50 kilometres of the beach and that number is slowly increasing.[i] Aside from the island of Tasmania, the states with the highest proportion of residents nearest to the coasts are those from the driest states, South Australia and Western Australia, where over 90% live in coastal regions. Even in the eastern states of Australia, where the outback is pleasantly habitable, over 80% choose to live close to the sea. This familiarity with the coast shows that most Australians are familiar with the most recognisable of ocean waves, the wind-generated wave.

Ocean waves aren’t all the same. Different forces generate different waves, but the wind is by far the primary driver of the waves we see crashing along Australia’s coast. Other effects include tidal movement, displacement of the seabed attributed to seismic or volcanic activity, iceberg calving and the occasional meteorite strike, all capable of causing pulsating waves in our oceans.

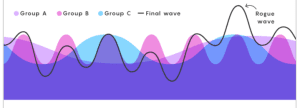

The very biggest of waves and swells occur when two separate wave events start overlapping (Figure 51). Invariably, different wavelengths result from waves being born from different wind strengths and differing weather events. Sometimes these waves merge cancelling each other out to smooth the surf. But 10 to 20 waves along, the amplitudes may align, creating enhanced wave sizes. A lot of discourse is paid to the subject of rouge waves, but in essence, these monsters are short-lived aberrations of ocean swells. When wavelengths align as coastal surf, beachgoers refer to this as the well-known ‘set of waves. It’s where two to five waves are far greater than the rest. Professional surfers learn to look at the duration of these sets to assess the best wave selection.

Three separate ocean swells merging. Image: Quanta magazine

In Australia, the debate rages about where the biggest waves are, but one surf break in Western Australia is held in the highest esteem by big wave junkies. Gracetown is a pretty little community on the coast at Cowaramup Bay in Western Australia’s famous Margaret River region. Two kilometres offshore, a shallow reef is known as Cowaramup Bombora, also known as the Cow Bommie, produces mammoth waves. This reef becomes a magnet for big wave surfers, especially when great wintry swells sweep in from the Southern Ocean.

Largest breaking wave

In 2007, Damon Eastaugh won the highly prized, Big Wave Award, for conquering a wave estimated to be 14 metres high.[ii] Impressive enough, but still, the Cow Bommie has been touted as producing waves even greater than 20 metres high. While accurately measuring shore and reef breaking waves is difficult, many attribute Cow Bommie’s waves as the largest breaking wave in Australia. This mighty claim is contested by some surfers who assert that the surf break at Shipstern in Tasmania is the largest and heaviest in terms of volume.

Shipstern is located on the Tasman Peninsula, just south of the picturesque and haunting ruins of Port Arthur. The region’s towering dolerite cliffs provide an exceptional viewing platform when these giant waves arrive. As intense low-pressure systems progress eastward over southern Tasmania, they generate massive swells up the island’s east coast. At Shipstern, a sub-surface ridge of dolerite columns makes this famous surf break incredibly large, but also treacherous. Surfers must be towed onto these fast-moving waves before sliding down a multi-tiered wave face. This stepped wave appears to mimic the tiered dolerite columns below the surface. The Shipstern break is often described as a wave within a wave within a wave and navigating down the wave face through these steps is what usually bring surfers undone. Speeds of over 50 kilometres per hour can be achieved by surfers once at the bottom of the wave. I have it on good authority that you don’t want to spend too much time in the water at Shipstern; the area is a favourite haunt for seals and patrolling great white sharks.

It’s a 3,000-kilometre stretch of Australia’s southern coastline that produces the largest swells. That’s due to the entire Southern Ocean experiencing the world’s most constant winds, generating the biggest swells and the fastest ocean currents. It is the cold weather fronts attached to low-pressure systems that are responsible for the biggest waves.[iii]

Scientists are aware that wave energy is a highly untapped energy source far greater than that of wind and solar. Waves a far more energy dense that their wind and solar counterparts.[3] Australian swells have been measured and quantified into units of energy. In southern Western Australia, South Australia, Victoria and Tasmania, swell energy averages 25 to 35 kilowatts per metre. In comparison, southern Queensland and New South Wales experience swell energy that averages only 10 to 20 kilowatts per metre. In northern Australia, the swells drop considerably with an average power of fewer than 10 kilowatts per metre[iv].

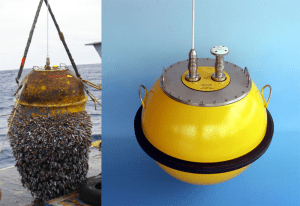

Australia’s, Bureau of Meteorology, in conjunction with various state governments, operate a series of waverider buoys to monitor wave heights and tsunami threats. Waverider buoys were first developed in the 1960s by a Dutch company in response to a calamitous flooding event that hit the low-lying Netherlands. Over 1,800 Dutch people died when a 1953 storm breached the coastal dyke defences. While the waverider buoys were first designed to save lives, the surfing community now eagerly disseminates information gathered to predict surfing conditions and wave size.

Largest wave

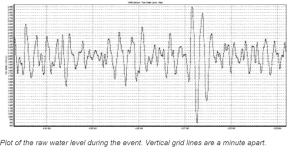

So far, Australia’s largest wave registered by this hi-tech gadgetry occurred when a deep low-pressure system embedded in the roaring forties, passed by southern Tasmania. On the 6th of August 2012, Maatsuyker Island off the state’s south coast received wind gusts of up to 154 kilometres per hour. The Bureau of Meteorology’s waverider buoy at Cape Sorell buoy lies 10 kilometres west of Cape Sorell, the major headland near the entrance to Macquarie Harbour. This buoy was recording huge swells when swell systems merged creating a mammoth 22.03-metre-high wave in the open sea. This wave smashed the previous record of 19.83 metres high registered by the same waverider buoy in 1982

Plot of the six minutes around the recording of Australia’s biggest ocean wave

Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology rates waves above 10 metres as ‘Very high’, and anything over 14 metres rates as ‘Phenomenal’. The world’s largest wave was measured from a fixed oil drilling platform in the North Sea. Dubbed the ‘Draupner wave’, it struck on New Year’s Eve, 1995 and measured 25.5 metres in height.[vi]

Largest tsunami waves

The largest tsunami officially recognised in historical times was one that impacted Alaska’s Lituya Bay in 1958.[viii] An earthquake sent a massive landslide into the bay, sending displaced water rushing down the bay and washing completely over islands in its path. The landslide occurred at the head of the bay, a location where two glaciers meet. This surrounding topography magnified the landslide’s splash, allowing the wave to travel upslope for an incredible 500 metres. The tsunami wave stripped vegetation off the hillsides as it passed, leaving a path of destruction still evident today. Geographers refer to these tell-tale paths of vanquished vegetation as trimlines. The tsunami continued along Lituya Bay releasing its energy as it went. The tidal wave height was estimated to be 25 to 30 metres at the bay’s seaward end, where it easily washed over small islands at the entrance. Graphic accounts appear online of a fishing boat surviving the tsunami, which testifies to the speed and ferocity of these waves.

The vast majority of tsunamis that have struck Australia are a result of tectonic events in the neighbouring countries of Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and New Zealand. It’s not just overseas tectonic activity, Australia is also capable of producing its very own domestic tsunamis. Despite the continent’s relatively stable tectonic history, the close proximity of Australia’s continental shelf can also generate slippages, which would certainly have devasting localised effects on today’s coastal regions.

The most famous tsunami event in modern Australia happened in 1938, at Sydney’s Bondi Beach.[ix] Over 250 beachgoers were dragged into the surf as three large waves engulfed the famous beach in quick succession. Today’s beachgoers can view a monument on the sidewalk, just before the famous Bondi Icebergs, commemorating five people that drowned on this fateful day. A day that locals have come to be known as Black Sunday. This tsunami was only a small event, but it happened on a crowded summer weekend as many beachgoers flocked to Bondi Beach. Australia has been fortunate not to have seen more tsunamis along the crowded east coast, for there is evidence of numerous significant tsunamis in recent geological history.

Scientists examine the alignment of rocks and washouts to determine if paleo-tsunamis have inundated areas. Enormous storms that generate powerful surf can move many large beach rocks around, but the ability to throw up enormous boulders onto beaches and rocky headlands require the force that only a tsunami can produce. Numerous examples of extremely large boulders, including the Cable Beach rock, near Albany in Western Australia, owe their placement to these mega-waves.

The section of the Australian coast most at risk from tsunami inundation happens to be the north-west coast of Western Australia, from Exmouth to Broome.[5] Since 1858, an estimated 10 tsunamis have left their mark on this coastline, including a giant wave generated by the Krakatoa eruption in 1883.[x] It goes without saying that having the world’s most active tectonic region, the Sunda Trench, directly to the north, has towns along this coast on constant tsunami watch. The biggest saving grace for these communities is that the North-west Shelf of Australia has the effect of dampening the tsunami’s power. In open oceans, tsunamis can travel at up to 500 kilometres per hour, but when they reach shallow waters like the North-west Shelf, friction slows the wave to just 50 kilometres per hour.[xi]

All these tsunamis pale in comparison to the mega-tsunamis caused by meteorite impacts. The tsunami generated by the Chicxulub meteorite no doubt contributed to the extinction of dinosaurs, along with re-aligning the fortunes of many plant and animal families. The impact into the shallow seas of the Yucatan Peninsula in modern-day Mexico would have produced a series of super-enormous waves, with estimations of heights varying from 50 metres to over 300 metres tall.[xii] These would have pulsated around the world for weeks before dissipating. Nobody wants to bear witness to this in their lifetime.

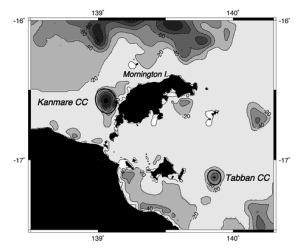

Ted Bryant from the University of Wollongong says that meteorite-producing tsunamis may be more common than we think. He and a crack team of geophysicists have identified a series of chevron-shaped sandhills that point directly to two meteorite craters buried in the waters beneath the Gulf of Carpentaria, straddling Mornington Island’s coast to the east and west.[xiii] The research team believes the impact site yields a date of 572AD+ 86 years. A date that roughly aligns with a global cooling event in 536AD. This was a year when crops were said to have failed and historical text noted a veil about the sun. Researchers identified two large craters, now called Kanmare (meaning Serpent), at 18 kilometres wide and Tabban (meaning Rainbow), at 12 kilometres wide, on either side of Mornington Island, as suspected culprits. They proposed that the meteorite was a 600-metre-wide comet that broke in two above Australia. Both pieces crashed into the Gulf of Carpentaria’s waters, causing tsunamis. The Kanmare tsunami resulted in the development of a series of chevron or V-shaped dunes. These dunes come about when enormous waves overwhelm and swamp coastal dunes and then backwash back to the sea. The dunes at Groote Eylandt, other dunes on Vander Lin Island and others north of Roper River, point directly at the Kanmare impact sites. Indigenous stories of shooting stars, booming noises, rising seas and bright lights appear to correlate with this historical event. While the evidence seems to point to an asteroid impact forming these depressions off Mornington Island, still more research must be undertaken to establish a definitive link between the chevron dunes and the cooling event of 536AD.

Largest open ocean wave recorded

Cape Sorell waverider buoy. 22.03 metres. 6 August 2012.

(Source: Bureau of Meteorology)