GEOGRAPHIC EXTREMES SOCIETY

AUSTRALIAN RECORDS

Rainfall

The rainfall reports of Australia are widely published and the records highly revered, so you would think that this would be straight-forward, well nothing could be further from the truth. I was about to discover the rainfall record mired in the egos of two long-deceased weather-men.

The highest rainfall in a single day

Crohamhurst Controversy

It was a locality called Crohamhurst. a rural backwater of the Sunshine Coast, that the record for the highest rainfall in a single day occurred in the 1890s. The title of ‘most rainfall in a day’ is the Holy Grail of climate records in Australia. On February 3, 1893, twenty-year-old Inigo Jones, who had recently had his meteorology career terminated at the Queensland Office of Meteorology, recorded an incredible 907mm of rainfall in a single day, which covers the periods from 9 am to 9 am.

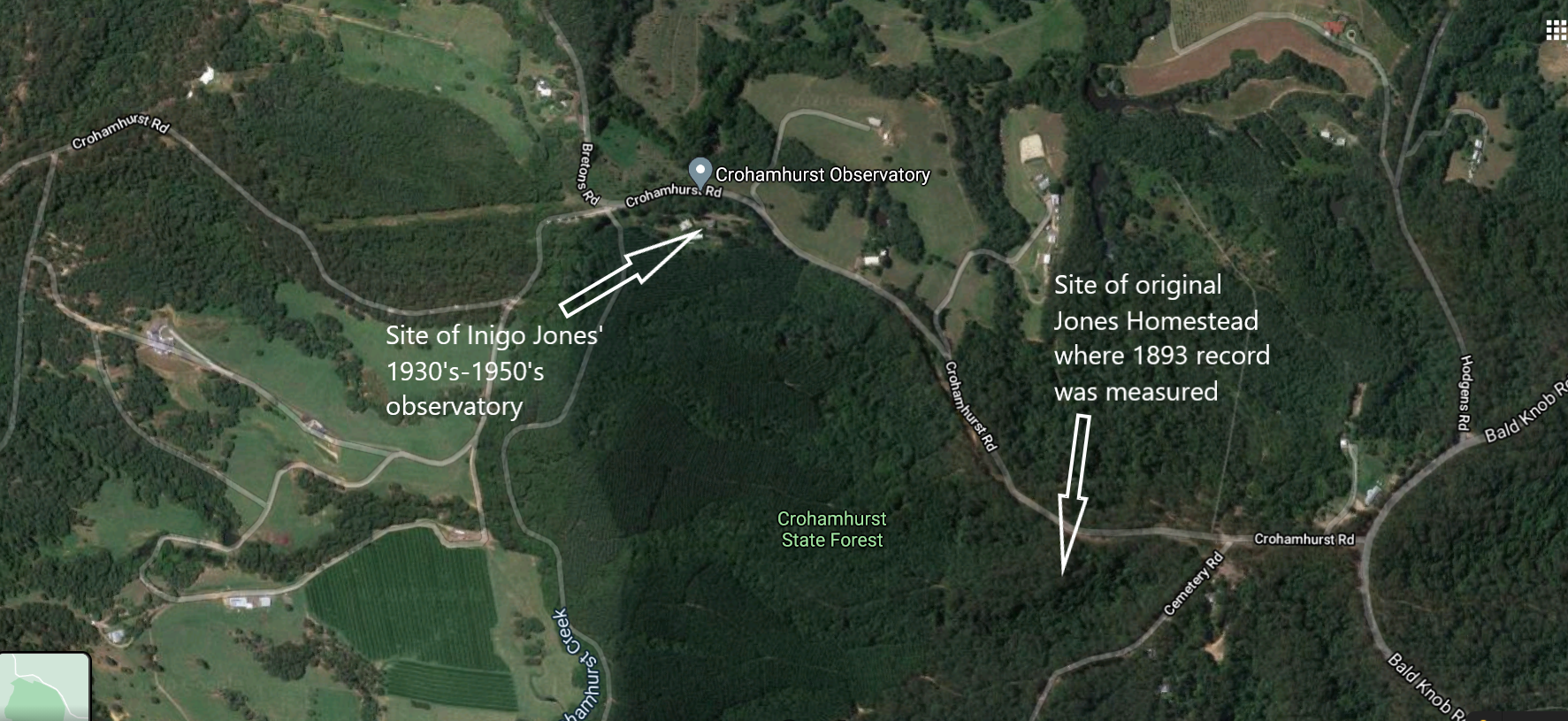

Map of Crohamhurst, highest single-day rainfall. Image: Google Maps

The Brisbane River flooded three times in February 1893, causing massive devastation in the northern colony’s largest city. During this time, two tropical cyclones and an associated east coast low battered central and south-east Queensland before continuing the destruction into the Northern Rivers of New South Wales. The enormous Brisbane River attained its second-largest river height in historical times, and numerous lives were lost. The deluge saw thousands of buildings and homes inundated, bridges swept away, and ships washed up on dry land.

A 907mm downfall is an extraordinary amount of precipitation. It is like emptying your swimming pool on one day, and the next day coming back to find it full to the brim again twenty-four hours later.

Over the years of my research of Australia’s rain events, my instincts told me that something was wrong with the Crohamhurst record. Surely the Top Station near the peak of Mount Bellenden Ker would surpass all other stations for the total daily rainfall, and in some books it does. Ian Read in his original book ‘Continent of Extremes’ has mistakenly given this title to Bellenden Ker. For an insignificant locality in south-east Queensland to hold the daily rainfall record just felt wrong, so I dug deeper. I discovered the rainfall record to be highly tarnished by those who recorded this event.

Allow me to describe how the 1893 rain event unfolded. On January 30, the Steamer MV Buninyong was lying in the lee of the Percy Group of islands, about 200km south-east of Mackay. Onboard this Queensland colonial government ship was the renowned head of the Queensland Meteorological Service, Clement Wragge, who was travelling from Mackay back to Brisbane when the oncoming Tropical Disturbance, or today’s Tropical Cyclone, passed over the ship. The winds had picked up, and the barometer plummeted, forcing the MV Buninyong to seek protection in the lee of the Percy Group of Islands. The tropical cyclone crossed the coast around Shoalwater Bay before tracking on a southerly inland course and turning into a tropical depression. This tropical depression continued south following a well-worn cyclone corridor down coastal Queensland, before merging with an East Coast Low. It was this combined system which was directly responsible for the tremendous amount of rainfall that south-east Queensland and northern New South Wales received.

It is when the system approached the Sunshine Coast that all the discrepancies began to arise. Almost every rain gauge recorded the majority of rainfall by 9 am on February 2, before the rain started to taper off. The one striking exception was the lone rainfall report from a gauge at Crohamhurst where the rainfall didn’t decrease on February 3 – instead, it almost doubled from the day before.

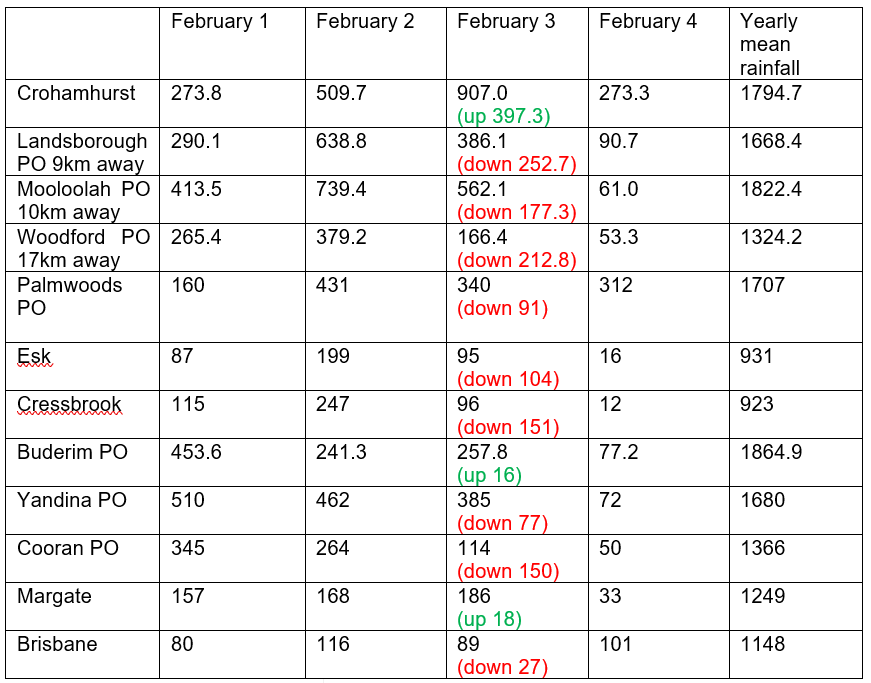

The rainfall discrepancy is singularly the most baffling of all the Bureau’s records. Landsborough, which is only 9km away, received the majority of its rainfall on Feb 2 with 638mm, almost halving to 386mm on February 3. On the other side of the range, the story is the same. Woodford saw a drop of 212mm from one day to the next, with 166mm in the gauge. Other nearby rain gauges repeat the same story, as the table below shows.

Approx locations of townships. Image: Google Maps

Courtesy of Bureau of Meteorology

Table 1. Daily Rainfall Totals for stations around Crohamhurst. February 1 – 4, 1893

Every locality surrounding Crohamhurst recorded less rainfall, almost halving their precipitation for the 24 hours up to 9 am on February 3. There were two small exceptions in the coastal rain gauges of Buderim and Margate, but these more or less indicate the system had moved offshore. Incredulously, Crohamhurst records a massive increase of almost 400mm. The absurd rainfall disparity is an incredible 500mm more than the traditionally wetter gauge to the east at Landsborough, and a phenomenal 750mm over Woodford to the west.

While rainfall anomalies amongst nearby rain gauges can be quite the norm, having a 500mm difference within a 10km radius is virtually unknown, especially for rain gauges that receive similar amounts of annual rainfall. Trawling through the climate records for the same month, another example of errors from this site emerged later in February 1893, when more exceptional rain deluged south-east Queensland. It seemed several rainfall logs from Crohamhurst were erroneous in February 1893.

Table 2 shows that records are all over the shop in Queensland in February 1893. On February 18, Landsborough received 10mm of rain while 10km away Crohamhurst received a massive 400mm.

Most would believe this was due to a simple case of observer error but this is where things start to get interesting. The Crohamhurst rainfall gauge had only started taking rainfall records on January 2 in 1893 and incredulously, only a month later, it recorded an all-time Australian record. It may have been the case of the person recording being a little too eager to impress the Chief of Meteorology at the time. If we look into the characters behind this record, the floodwaters muddy still further.

Clement Wragge, who was on MV Buninyong at the time of this flooding and rainfall event, was a true icon of the meteorological world whose legacy survives to this day. It was in 1887 he became the Chief Meteorological Officer in the Queensland Colonial Government’s Meteorological Division. Wragge brought great zeal to the position, and with his remarkable scientific mind, he soon surpassed all others in his field, becoming the pre-eminent meteorologist throughout the Australian colonies and into the south Pacific.

The 1893 rain event, during which Clement Wragge was on the MV Buninyong, has now been retrospectively named TC Buninyong by some retired members of the Bureau staff. Still, I suggest a better name would have been TC Dicky after the ship the SS Dicky, whose hull left a lasting legacy for over 120 years when it ran aground, in the same storm, on what is now Dicky Beach at Caloundra. Upon weathering the 1893 tempest at sea, Clement Wragge sailed on to Brisbane. One of his first actions was to send a telegram up to Mr Owen Jones, the owner of Crohamhurst and father to a young, later to become infamous, Inigo Jones.

Clement Wragge and Inigo Jones were well known to one another. The young Inigo Jones met Clement Wragge when completing his final years of schooling at Brisbane Grammar School. In 1887, the eager schoolboy pestered Clement Wragge to present Inigo Jones with a full set of meteorological observation equipment, which he did. Jones eventually impressed the Chief of the Meteorology Division so much that the 15-year-old boy was offered a cadetship at the Queensland Meteorological Service, once he had finished his high schooling. With this offer in mind and his life’s passion realised at such an early age, Inigo Jones passed up a position at the University of New South Wales and decided to instead join Wragge as his assistant at the end of 1888.

Clement Wragge at this time had been ordered by the Queensland Colonial Government to examine the Bruckner Cycle. We came across Bruckner’s thirty-five-year cycle in chapter 1. Eduard Bruckner had been researching the effects of planetary magnetism on Earth’s weather in the hopes that a pattern would reveal itself, and the Queensland government hoped this research would assist the burgeoning agricultural sector. From the very beginning, the work fascinated young Jones, and it remained his principal obsession until the day he died. Inigo Jones’s tenure at the Meteorological Service lasted for four years before he unexpectedly left to join his family as a farm boy at a property called Crohamhurst in the Glass House Mountains.

Nothing is known as to the reasons Inigo Jones stopped working with the Queensland Meteorological Service, but to leave a government scientific position to become a farm boy seems rather strange. His father was an engineer and his mother came from a line of famous mathematicians. They must have had lofty ambitions for their only child as his parents named him after the renowned fifteenth-century architect, Inigo Jones. One would imagine that Jones didn’t resign a scientific position willingly, in favour of milking cows, because this was his dream job and what was to become his life-long career.

Even though Jones moved out of Brisbane, he wasn’t ready to give up on meteorology. He started taking readings at his parents’ property where, lo and behold, he recorded the national rainfall record only a few weeks later.

Was he trying to better his old boss, Clement Wragge, who in 1887, had also recorded the largest rainfall in a day at his property in the Brisbane suburb of Taringa? Well, I know a lot of strange things happen, but coincidence? I suspect not. Jones’ record of 907 millimetres was astounding. It crushed every record for 130 years.

In retrospect, it sounds like a discarded employee letting his old boss know he was still around. That urgent telegram sent by Clement Wragge when he disembarked the MV Buninyong, was sent not to his former assistant and work colleague, but Inigo’s father. Owen Jones also had to rely on the word of his son that he had risen multiple times throughout the night to empty the almost over-flowing rain gauge, that measures only twelve inches or 300mm of rainfall at a time. One might suspect that Wragge had lost faith in young Jones.

There is some corroborating evidence of a significant flood coming down the Stanley River by way of Crohamhurst, but the timing of the surge doesn’t correspond to the rainfall peaks. Inigo Jones hadn’t even finished tallying the daily rainfall, when the floodwaters had travelled over 100 kilometres downstream and halfway to Brisbane.

Mr Somerset was the owner of Caboonbah Station where the Stanley River meets the Upper Brisbane River, and he noted the following on the early morning of February 3, before Jones had made the final rainfall reading. He wrote … “I heard a louder noise, quite different and a wall of water fully fifty feet high coming around the bend (of the Stanley River.” That flood peak took another two days to travel the final 150 kilometres to the centre of Brisbane. If Jones was correct, it seems that the flood peak slowed considerably once past Caboonbah, My best guess is that the most considerable rainfall occurred before February 2 allowing time for the water to build up, before making its way down the Stanley River towards Mr Somerset’s property.

Wragge eventually accepted the rainfall on the word of Inigo’s father and later supported it with an entry in the journal Nature. Still, the article never mentions Jones by name and Wragge mostly takes much of the credit for himself.

Inigo Jones drops off the radar for nearly three decades following this, before taking up his passion once more. Again, it appears odd that only when Wragge passed away in 1922, that Inigo Jones released his first long-range weather forecast.

Jones went on to establish a cult-like following as a long-range weather forecaster amongst a large swathe of the Australian public. His belief lay in a solar-system-wide electromagnetic field which affected the weather differently throughout the country. To the dismay of some, he also believed that certain places on Earth, like Crohamhurst, had unique influences from the pulses of this mysterious cosmic energy. No one in the scientific community could understand his errant methodology. However, in the public’s eye, this self-assured scientific figure offered hope, especially during the years of the Great Depression. He cultivated this image of a trust-worthy gentleman of science who had made advances in meteorology. Jones was able to sell his long-range weather forecasts to newspapers and magazines throughout Australia.

Some have called Inigo ‘the prophet of long-range weather forecasting’ while others have written off his life’s studies as dangerous forecasting, that lured unsuspecting farmers to their ruin. He certainly had a lot of admirers of his work, all the way up to the highest echelons of power.

Today, the Crohamhurst site is a run-down shell of the heritage-listed Crohamhurst Weather Observatory. A grant from the agricultural and mining giant, CSR allowed Jones to establish his observatory in 1935 to assist in his rainfall predictions. There still remains the 8-inch rain gauge used for recording the rainfall in 1893, and the numerous articles Jones collected about himself for future posterity. Adorning the walls were images of notable scientific minds from Pythagoras to Copernicus, Galileo and Newton. I stood there pondering if Inigo Jones thought that his portrait would one day live alongside these scientific greats.

I have written about this record further in other blogs and in the book ‘Life In The Extremes’ but all in all, I would argue that the Crohamhurst record is decidedly suspect, and as soon as practicable, should be withdrawn. It fails on a number of levels

- When compared to adjacent meteorological stations,

- The timing of floodwaters down the rivers,

- Jones’ record-keeping for the whole month,

- The circumstances behind the establishment of the Crohamhurst gauges and his apparent falling out with Clement Wragge.

What, in its place, would then be the record for the wettest day in Australia? For that, we have to turn our attention to the Bellenden Ker Top Station in Far North Queensland.

Alternative record

The site of this rainfall station is 1,545m above sea level, cradled on a narrow ridge upon the second tallest mountain in Queensland, Mount Bellenden Ker. Atop this mountain is undoubtedly the wettest meteorology station in Australia. It averages a mean rainfall of 8,053mm per year, almost double that of any other rain gauge in Australia. The reason for the abundant rainfall is the aspect of the Bellenden Ker Range which runs in a north-south direction, from above Innisfail to below Cairns. It includes the notable peaks of Queensland’s tallest mountain, Mount Bartle Frere, the more considerable but only a few metres shorter, Mount Bellenden Ker, and Walsh’s Pyramid – what some claim to be the tallest free-standing mountain in Australia. The height of these peaks and the north/south orientation of the range ensures the mountains perfectly capture the moisture-bearing winds coming off the Coral Sea. The moisture-laden clouds release torrents of rain as they push over the ranges and on to the Atherton Tablelands. The station is only accessible by a 6km-long cable car service operated by the Canadian-owned company, Broadcast Australia, who operate television towers and communication transmitters from the peak.

I had always wanted to travel on the cablecar to inspect the rain gauges at the Bellenden Ker Top Station. Just getting access to the cable car is tricky. Being a private operation, only a handful of non-employees get to travel up to the Top Station every year. In the end, I strike it lucky, and after a series of safety inductions, I’m allowed to go up and inspect Australia’s wettest rainfall station.

Finding rainfall records here is easy. The Bellenden Ker Top Station owns every rainfall record except for the Crohamhurst highest daily total. Some publications and websites state the record daily rainfall for Australia was recorded at Bellenden Ker Top Station on January 4, 1979, with 1,140mm recorded for the day. Still, the archives from the Bureau of Meteorology don’t corroborate this. Bellenden Ker Top Station is a manual station, and the team who work the cable car to the top station don’t work every day, so sometimes there is an accumulated total of rainfall over a few days. The archive shows that no one visited the weather station on January 4, but that on January 5 the rainfall was … 1,947mm! Rainfall of this magnitude is more than Melbourne, Adelaide and Hobart combined, in just 48 hours. If you were to divide this total over the two days, the resulting 973mm beats the Crohamhurst record of 907mm by a considerable margin. These circumstances of two accumulated rainfall days surpassing the Cromhamhurst record of 907mm has occurred twice in the station’s history.

Bellenden Ker Bottom Station, located at the bottom of the cable car, recorded a massive 1,196mm over the two days of January 4 and 5, 1979, with 756mm falling on January 5. It leads me to believe that January 5 was most likely the most considerable rainfall at the Top Station, and probably the biggest total in Australia’s recorded history. But only if there is someone there to record it.

I have made it my mission to visit the sites of Australia’s Geographic Records, so was lucky enough to gain access to the Mount Bellenden Ker Top Station. It is a twenty-minute journey up Bellenden Ker by cable car. As we approached the Top Station, I enquired to the location of the rain gauges. Our guide pointed to the spot… and my heart skipped a beat.

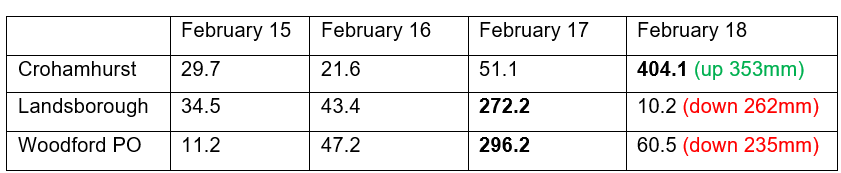

Bellenden Ker Top Station site plan. Image: BoM website info for site 031141

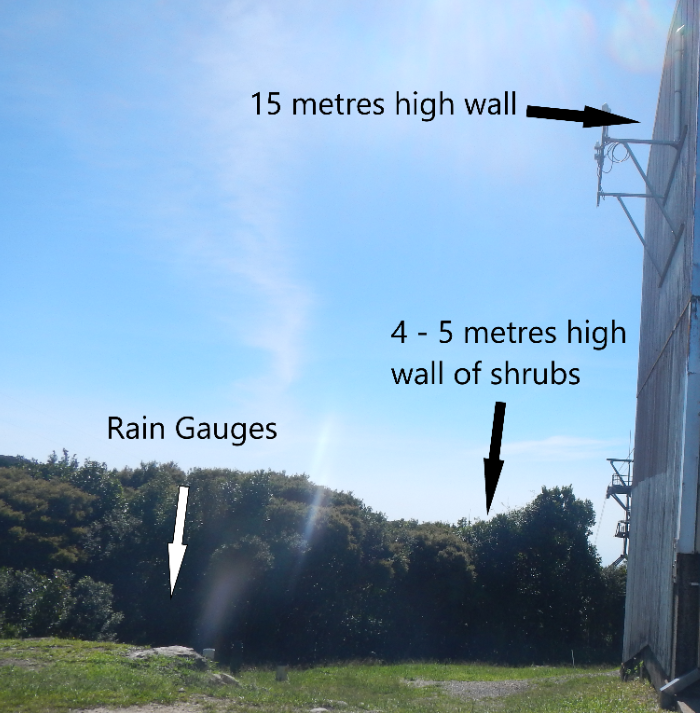

I didn’t know what to say and just stared at the location of the gauges with my head spinning. The siting of the gauges are within seven metres of the building housing the colossal cable car and its associated pulleys and machinery. What proved to be a solid fifteen-metre high wall lies within only a half dozen steps from the rain gauges. The dense vegetation forms a hollow around the rain gauges, certainly allowing wind currents to influences readings.

We pulled in to the Top Station building and exited the cable-car. I walked directly to the rain gauges, looked at the high wall next to it and let the consequences of this revelation sink in. The weather station holding the greatest number of rainfall records in Australia is utterly compromised. Its positioning fails to meet the Bureau’s guidelines for siting of a rain gauge by a considerable margin.

What was it with Australia’s rainfall records? Once again, after careful examination, the record is in disrepute. We can all forgive many of the rainfall stations in Australia which don’t comply to the letter of the law when it comes to the positioning of rain gauges, but for the gauge which holds the majority of rainfall records to be so far compromised is not acceptable.

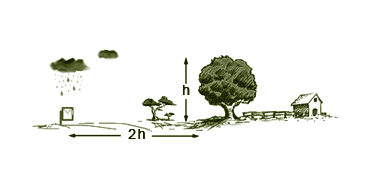

The Bureau of Meteorology has set exacting guidelines as to the positioning of rain gauges and this site, the very site that has every Australian rainfall record bar one, fails these guidelines by a significant margin, as shown below.

Installing a Rain Gauge

Gauges sited near buildings, solid fences and trees can have serious errors in rainfall totals. The distance of the gauge from buildings, trees or other objects should be at least twice the height of the obstruction, and preferably four times the height. For instance, the gauge should be more than 10 metres from a house 5 metres high and more than 30 metres from the nearest branches of a tree 15 metres high. The gauge should also be in a place where it will not be disturbed by people, animals or vehicles.

[Courtesy of the Bureau of Meteorology website.]

According to the Bureau’s criteria, the rain gauge on top of Mount Bellenden Ker the location should be at least thirty metres away from the fifteen-metre-high wall and 10 metres from the wall of shrubs. In all fairness, environmental restraints imposed by National Parks have restricted site selection options for the rain gauges here. The station is amongst the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area, a biological crown jewel for Australian natural history. The peaks of these mountains host a range of sensitive and endangered fauna and flora, many species of which have close relatives that go back hundreds of millions of years. With today’s commitment to world’s best practice conservation, you would no longer be allowed to build these communication towers nor establish a cable car to service it. Just clearing another site to conform with the Bureau’s guidelines is bound to be hampered by green tape.

The ramifications for removing the Bellenden Ker Top Station rainfall records are enormous.

Highest Monthly Rainfall

The record previously was at the discredited the Bellenden Ker Top Station, the Bellenden Ker Bottom Station will attain the title for the highest monthly rainfall at 3,075.5mm in January 1979.

Highest Yearly Rainfall

The record previously was at the discredited the Bellenden Ker Top Stations. Tully lays claim to the record for the highest yearly rainfall, with 7,898mm falling in 1950

Tully’s Golden Gumboot. Highest yearly rainfall record. Image: RJ Andrews

Highest Rainfall in a single day

What of the holy grail of climate records, the largest rainfall in a single day? If we were to dismiss the Bellenden Ker Top Station records, and repudiate the Crohamhurst/Inigo Jones figures, the record would have to be passed instead to Finch Hatton in the Pioneer Valley west of Mackay, for a recording of 878mm on February 18, 1958.

Original Finch Hatton Post Office. Highest daily Rainfall recorded here in 1958. Image: Realestate.com

Wettest Town in Australia

Every year the Golden Gumboot award gets passed out to the post in a town with the wettest yearly rainfall. For the vast majority of the years, Babinda at the Base of Mount Bellenden Ker wins the record.

Golden Gumboot sits proudly in the Post Office window in Babinda: Image: RJ Andrews

Most number of wet days

Queensland and the tropics aren’t the only exceptional wet areas, Dorrigo in New South Wales and the west coast of Tasmania received incredible amounts of rain. The temperate rainforests of Tasmania are also very wet places. In areas like Lake Margaret, Roseberry and Waratah, the number of days with rain far exceeds the sunny days. The cold, wet days feel, smell, and sound quite different from the Wet Tropics.

Rainfall Records

Highest 24-hour rainfall. Crohamhurst Feb 3, 1893 – 907mm – discredited due to observer error

Highest 24-hour rainfall. Bellenden Ker Top Station – Jan 4 & 5, 1979 – 1,947mm over two days – compromised recording apparatus

GES Record: Highest 24-hour rainfall. Finch Hatton. February 18, 1958 – 878mm (Source: Bureau of Meteorology)

Highest monthly rainfall – Bellenden Ker Top Station – January 1979 – 5,370mm compromised recording apparatus

GES Record: Highest monthly rainfall – Bellenden Ker Bottom Station – January 1979 – 3,075.5mm (Source: Bureau of Meteorology)

Highest annual rainfall – Bellenden Ker Top Station – 2000 – 12,461mm. compromised recording apparatus

GES Record: Highest annual rainfall – Tully. 1950 – 7,898mm (Source: Bureau of Meteorology)

GES Record: Wettest town. Highest mean rainfall – Babinda – 4,269.7mm (Source: Bureau of Meteorology)

Australian State / Territory Records (source: Bureau of Meteorology)

Australian Capital Territory – BoM has tended to lump ACT’s data into NSW

New South Wales – 21 Feb 1954. Dorrigo (Myrtle St). 809.2 mm

Northern Territory – 15 Apr 1963. Roper Valley. 544.6 mm

Queensland – 18 Feb 1958. Finch Hatton. 878 mm (revised after disputed records)

South Australia – 14 Mar 1989. Motpena. 272.6 mm

Tasmania – 22 Mar 1974. St Mary’s (Cullenswood). 352 mm

Victoria – 22 Mar 1983. Tanybryn. 375 mm

Western Australia – 3 Apr 1898. Whim Creek. 747 mm

The Geographic Extremes Society welcomes any input as to the veracity of these records and we encourage everyone to contribute to these extreme records by contacting us to initiate the discussion