GEOGRAPHIC EXTREMES SOCIETY

AUSTRALIAN RECORDS

Reflectivity

Australia’s lakes come in all different shades of the rainbow. Turbid waters within dams exhibit many earthy colours of reds, yellows and browns, gained from surrounding soils. The higher the algal content, the greener they become. The traditional blue colours are attributed to the natural reflections from the sky, through what we call Raleigh scattering. In contrast, the chalky-blue waters of Rapid Bay in South Australia and the Pomio River in New Britain get there blue from weathering of limestone deposits. Dark red and pink colourings arise from micro-organisms and some forms of mineralisation. Some black water lakes have vast amounts of leeched tannins staining the water, turning them from dark brown to inky black. By contrast, the brightest and whitest lakes are salt lakes.

So, what else might influence these coloured lakes? The water that falls from the sky is of a single, consistent colour, but a combination of the chemistry, biology, and soil types contribute to the colours we perceive.

To explore this fascinating subject, let’s firstly tackle the brightest whites emitted by salt lakes. For this, we have to get to the home of salt lakes, South Australia, where the most brilliant places on earth, Lake Frome resides.

The view of Australia, as seen from space, or Google Earth, is of a predominately brown continent with conspicuous bright spots, the white salt lakes, which capture your attention. However, they’re not all as bright as each other. While Lake Gairdner and Island Lagoon, also in South Australia, show up as being highly reflective, it is indeed Lake Frome that appears the brightest of all from space. The Satellite imagery we see has an incredible range of applications for governments and industry. From high above in Space, satellites garner insights on the planet depending on wavelengths of light captured.

The boundary of Earth’s atmosphere and space, or what the aerospace community calls the Karman Line, starts at about 100km above sea level, making it nice and easy to remember for non-astrophysicists like myself. Satellites sent into space orbit between 500-300,000 kilometres above the planet. Matching the pace of the spinning Earth, geostationary satellites are fixed to what is known as a geosynchronous orbit at 35,786 km above sea level.

The brightest spot on Earth

In January 2000, NASA launched its new generation of Earth Observation Satellites and chose various locations around the planet to test their ultra-sensitive Hyperion sensors. These satellites employed the latest visual wizardry to enable scientists, researchers, and government bodies to analyse soil, water, vegetation, and changes in the atmosphere. From a long list of candidates, NASA chose at the top of its list, the bright, white surface of Lake Frome to assist in the calibration of these sensors. The Hyperion sensors aboard NASA’s EO-1 satellite utilise over 220 spectral bands of light for their imaging and to adjust the sensors’ white balance, they required an extremely white, reflective, and uniform surface.

The opportunity arose for the brilliant Australian scientists to contribute to the advanced spectral imaging of Earth. The CSIRO stepped in to help test this new generation equipment and sent a team of scientists, headed by Susan Campbell, to Lake Frome.

Lake Frome from Space. Image: Google Maps

The secret to Lake Frome’s bright salt pans is the scarcity of the water entering the lake system. Strzelecki Creek might be the largest creek to inflow into lake Frome but most water comes from the infrequent rains into creeks out of the northern Flinders Ranges. The few feeding creeks which make it into Lake Frome drop their sediment load, resulting in quite clean water entering the lake. The ancient mega lake most often referred to as Lake Dieri is responsible for the accumulated salts. It once joined Lake Frome to Lake Eyre and included Lake Gregory, Lake Callabonna, and Lake Blanche nearly 50,000 years ago.

Lake Frome. The brightest spot on Earth. Image: CSIRO

The ability of landscape and surfaces to reflect the Sun’s rays is known as its ‘albedo’, and this is used by climate scientists to quantify the amount of light reflected into space, or more importantly, how much light is absorbed by surfaces. Lake Frome’s salt pans offer the most reflective surface in Australia and one of the most reflective surfaces on planet Earth, with over a constant 70% of the light which strikes the surface being diffused and reflected into space. Lake Frome’s albedo is more reflective than the Moon, at just 7-12%, snow, 30-60% and clouds, 30-70%. Satellites like NASA’s EO-1 give climate scientists unprecedented access to real-time sunlight absorption rates to help quantify Earth’s continually changing climate.

Lake Frome can alter colour depending on when the last inflow of water occurred, or when rain last fell onto the lake’s surface. During prolonged droughts, dust storms can coat the salt surface, staining it to a hue of reddish-brown. When water enters the lake, the micro-organisms blossom, feeding on the new nutrients blown in from the Flinders Ranges and beyond. Initially, the water appears to turn pink before gradually evolving to a green colouring, then eventually to blue. When the water eventually evaporates, all that’s left behind is the white, expansive salt crystal surface.

Darkest spot on Australian surface

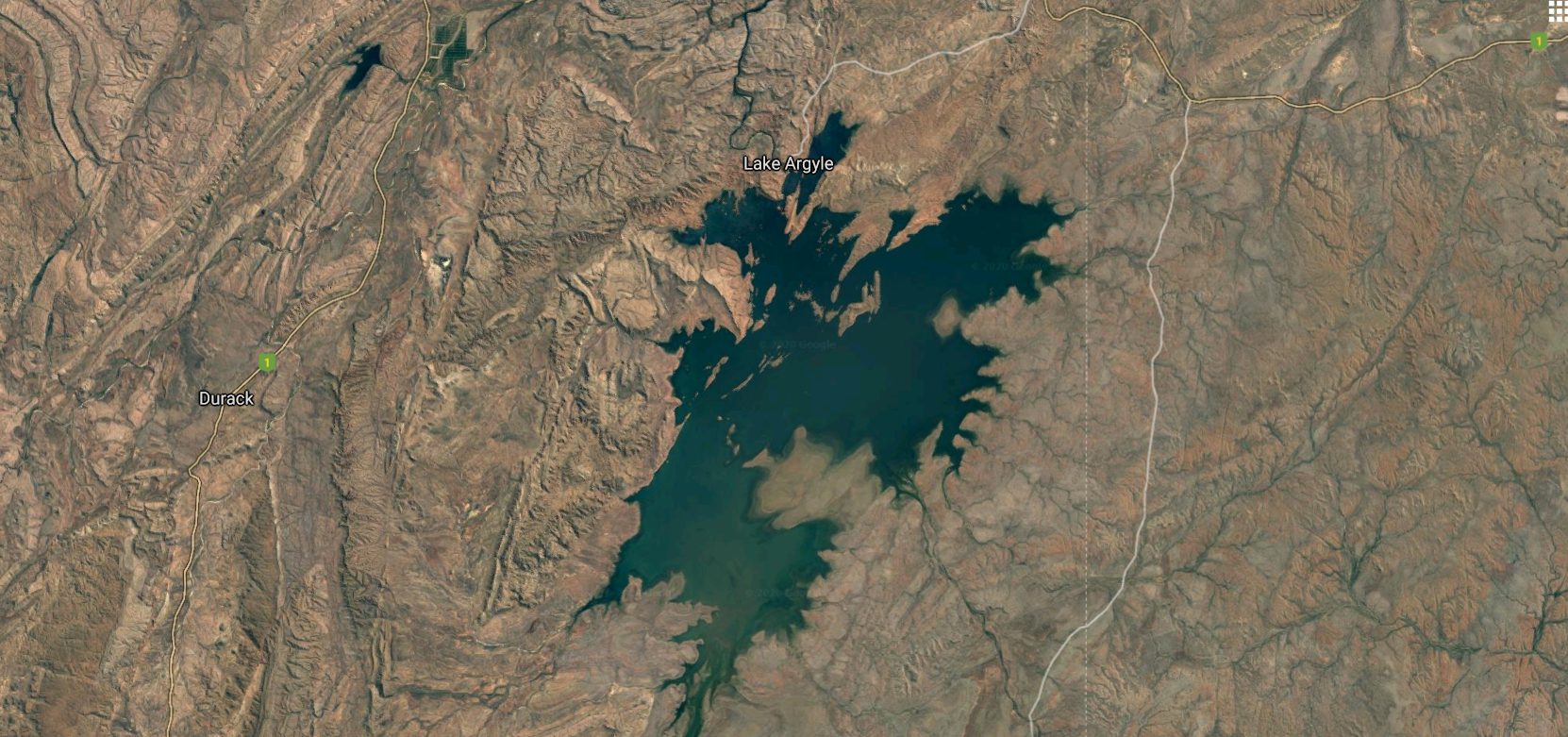

It was at Lake Argyle that the CSIRO determined what the blackest, or darkest spot, on Australia was via satellite. Lake Argyle in northern Western Australia, has an albedo of just 5%, meaning the lake absorbs a massive 95% of the Sun’s rays striking its surface.

Lake Argyle. Least most reflective water body in Australia. Image: Google Maps

Pinkest Lakes in Australia

Other lakes come in all colours of the spectrum. If you have ever wondered how to create the colour pink, especially the Hubba Bubba pink, it needs the extreme wavelengths of light from opposite ends of the visible spectrum, that is a mixture of ultra-violet and infra-red. For humans, our eyes are capable of determining colours of light between 380 and 740-nanometre wavelengths. Ultra-violet colours have a wavelength between 300 and 400 nanometres. At the other end of the visible spectrum for humans is infra-red light, which has a wavelength from 700 to 1000 nanometres.

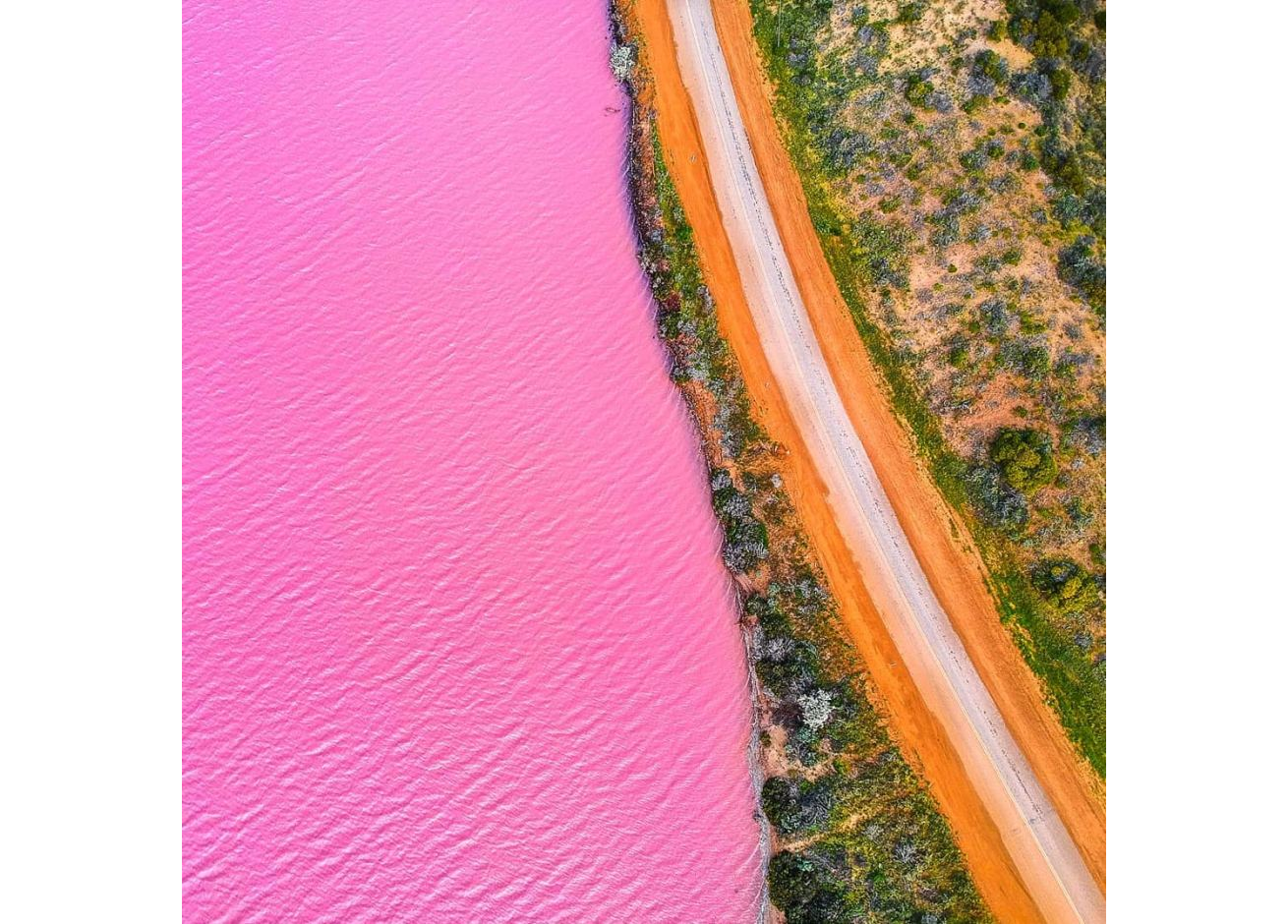

The pink lakes in Australia are astounding and are beginning to gain world-wide attention due to the power of photos on social media. Tourists from Australia and increasingly, Asia, flock to the shores of these waterbodies to take pictures of themselves dipping their feet in the pink brines. These lakes are not constant in their pink colouration, this varies during the daylight hours and from season to season, with summer providing the most vivid hues.

Hutt Lagoon. Image: ABC

Some pink lakes like Hutt Lagoon are now on well-worn tourist paths, but it is Lake Hillier in the south of Western Australia which is widely regarded by tourism authorities as to the pinkest of all the pink lakes in Australia. Located on Middle Island in the Recherche Archipelago, Lake Hillier is the jewel in the crown of this chain of islands that stretch for 230 kilometres east of Esperance.

Lake Hillier. Pinkest lake in Australia. Image:

The haloarchaeal organisms can turn lakes pink very quickly. In 2012, a salt lake next to Melbourne’s Westgate Bridge suddenly became pink to the amazement of Melburnians and the local scientific community. It seemed that nothing much had changed hydraulically at the site, but water temperatures had risen over the last decade. Every summer since, the salt lake in Westgate Park has turned pink, with the colouring fading by mid to late autumn.

Lake at Westgate Park. Melbourne. Image: ABC

Reflectivity records

GES Record: Pinkest Lake – Lake Hillier. Middle Island. Recherche Archipelago. Western Australia. (Source: RJ Andrews)

GES Record: Brightest spot on Earth from space – Lake Frome. South Australia. (Source: CSIRO)

GES Record: Darkest spot in Australia from space – Lake Argyle. East Kimberley. Western Australia (Source: CSIRO)

The Geographic Extremes Society welcomes any input as to the veracity of these records and we encourage everyone to contribute to these extreme records by contacting us to initiate the discussion